“God does not play dice. “

Albert Einstein

Imagine you’re at the blackjack table, you’re dealt a 10 and a 7 (hard 17), and the dealer shows a 10. This is a bad situation, but the odds say you stand and hope the dealer busts. You are about to do just that, but the drunk guy on your right says, “Hit, bro, I’m feeling a four.”

What are the odds this is good advice?

I’m too lazy to look up the exact odds, but let’s just invent some very rough approximations to illustrate the point.

Assume there’s a 50 percent chance you will lose no matter what you do, i.e., it makes no difference whether you hit or stand. That means there’s a 50 percent chance you win (or push) assuming you make the right choice. Let’s further assume if you stand, there’s a 30 percent chance you win (or push), and if you hit there’s a 20 percent chance you win or push. Again, please don’t quibble about the true odds in this situation, as it’s unimportant for the example.

With these odds, what are the chances hitting on hard 17 against a 10 is good advice?

Let’s make it multiple choice:

A) 20% (That’s your chance to win)

B) 0% (It’s always wrong to hit when your odds of winning are better if you stand)

C) 40% (To the extent your decision matters, it’s 2 out of 5 (20% out of 50%) that hitting will win you the hand.)

In my view, A) is the simple response, and it’s not terrible. It recognizes there’s some chance hitting in that situation gives you the desired outcome even if it’s not the optimal choice. It’s probabilistic thinking, which is the correct approach in games of chance, but just slightly misapplied.

B) is the worst response in my opinion. It’s refusing to apply probabilistic thinking in service of a dogma about probabilistic thinking! “It’s always wrong to hit in that situation” is an absolutist position when of course hitting sometimes yields the desired result. The “but my process was good” adherents love B. It signals their devotion to the rule behind the decision (the process) and avoids addressing the likelihood of whether the decision itself pans out in reality.

C) This is in my view the correct answer. To the extent your decision matters, there’s a 40 percent chance hitting will improve your outcome and a 60 percent chance it will not. I’m not looking for self-help or a remedial grade-school probability class. I don’t need to remind myself of what the best process is — I simply want to know my odds of winning money on this particular hand.

Let’s say it’s a low-stakes hand, you’re drunk, you take the advice for laughs, the next card is in fact a four, you have 21, the dealer flips over a 10 and has 20. You win, and you would have lost had you stayed. You high-five the drunk. What are the odds now you got good advice?

A) 0% — bad process!

B) 40% — same odds, don’t be result-oriented!

C) 100% — you already won!

The answer is obviously C. The point of the game is to win money, and taking his advice* on that particular hand did just that for you. You are not obligated to use that heuristic ever again. This isn’t a self-improvement seminar about creating better, more sustainable habits. You won the money, and now that you know what the next card actually was, it would be pathological to go back in time and not take his advice.

*You might think this is just a semantic argument — what we mean by “good advice” depends on whether it’s applied generally or specifically, and that is the distinction, but as we will see below the conflation of the general with the specific is itself the heart of the problem.

I use blackjack as the example because, assuming an infinite shoe (no card counting), the values of each card in each situation are well known. Coins, dice and cards are where simple probabilistic thinking functions best, where the assumptions we make are reliable and fixed. But even deep in this territory, it’s simple to illustrate how a focus on process is not a magic cloak by which one can hide from real-life results. If you lose the money, you lose the money. The casino does not allow you to plead “but my process was good!” to get a refund.

Of course, this one-off example aside, in the territory of cards and coins, the process of choosing the highest winning probability action, applied over time, will yield better results than listening to the drunk. But when we move out of this territory into complex systems, then the “but my process was good” plea is no longer simply falling on the deaf ears of the pit boss when reality goes against you, but those of the warden at the insane asylum.

. . .

I’ve encountered a similar strain of thinking on NFL analytics Twitter too. Sports analytics involve probabilistic thinking, but as leagues and teams are complex systems, it’s hardly as simple as coins and cards.

When Giants GM Dave Gettleman passed on Sam Darnold — the highest rated quarterback remaining on many boards — at pick 2 in the 2018 draft, and took generational running back prospect Saquon Barkley instead, the process people were aghast. How could you take a low-value position like running back over the highest value one when your team needs a quarterback? You always take the quarterback!

As a Giants fan, I was happy with the pick. My view was the same as Gettleman’s in this instance when he said something to the effect of, “If you have to talk yourself into a particular quarterback at that pick, pass.” His point was that he’d have taken a quarterback he liked there obviously, but he didn’t like the remaining ones, so he went elsewhere.

Now people were especially aghast he took a running back rather than say Bradley Chubb, an edge rusher, or Denzel Ward a cornerback, two typically higher value positions than running back, and those would have been good picks too, as both players have been productive in the NFL**. But Barkley has been as advertised when healthy, despite playing with a substandard supporting cast his entire career. He’s a good player, though a star running back obviously won’t singlehandedly transform a franchise the way a star quarterback might.

** The optimal pick would have been quarterback Josh Allen who went at No. 7, but was considered a reach by many in the analytics community because he was a raw prospect with physical skills, but lacked sufficient college production.

But how did the process choice, Sam Darnold, do? He was a disaster for the Jets for three seasons, destroying any hope they might have had at competing, though they salvaged some value by dealing him to the Panthers for picks. He’s also been bad on the Panthers, to date. So did Gettleman make a good choice, drafting one of the consensus top running back prospects of all time over the not-especially-impressive top-two quarterback prospect in that particular class? By any sane account, he did. He landed the better player, and while Chubb and Ward would have been fine, so was Barkley.

But despite Darnold’s failure as a prospect, the process people won’t take the L! They insist even though Barkley is a good running back, and Darnold a terrible quarterback, their process in preferring Darnold was good! But I don’t care about your process! The quality of your process will be adjudicated by your long-term results, the way a religious person’s moral character will be judged by his God. I have no interest in your attestations and signaling, no inclination to evaluate your lifelong body of work. We were simply debating this one particular pick, the results of which are already obvious to anyone not steeped in this bizarre worldview wherein you can claim vindication over reality a priori via believing you’ve found the right heuristic!

There are two claims they are making implicitly here: (1) That if quarterbacks are more valuable generally, you should always take the best available quarterback over the best available running back, irrespective of the particular human beings at issue; and (2) That no matter what the results were, you would be correct to have taken the quarterback.

Claim (1) is the notion that if something is generally — or on average — the case, the specifics need not be taken into account, i.e., they see players as having static values, based on their positions, like cards in blackjack. Claim (2) is the idea that only the heuristic should be evaluated, never the outcome. Taken together they are saying, always do what is generically most probable, ignore details and specifics and have zero regard for how any particular decision pans out in reality. In my view, this is pathological, but that’s okay, it’s only an argument about football draft analytics!

. . .

Our public health response to the covid pandemic increasingly appears to be a disaster. From lockdowns, to school closures, to vaccine mandates to discouraging people from getting early treatment, it has cost many lives, harmed children, wreaked havoc on the economy and done serious damage to our trust in institutions. Many of those who were skeptical of the narrative — for which they were slandered, fired from jobs and deplatformed — have proven prescient and wise.

While some holdouts pretend the covid measures were largely successful, most people — even those once in favor of the measures — now acknowledge the reality: the authors of The Great Barrington Declaration, which advocated for protecting only the vulnerable and not disrupting all of society, were correct. But I am starting to see the same demented logic that declared Darnold a better pick than Barkley emerge even in regard to our covid response.

Here’s a clip of Sam Harris insisting that even though Covid wasn’t as deadly as he had thought, he would have been right if it had been more deadly. (Jimmy Dore does a great job of highlighting the pathology):

Harris is arguing that even if the outcome of our response has been catastrophic, that’s just results-oriented thinking! He still believes he was staying on 17, so to speak, that he made the right call probabilistically and that he was simply unlucky. (Never mind that locking down healthy people was never part of our traditional pandemic response playbook, and coerced medicine is in plain violation of the Nuremberg Code, i.e., he wasn’t advocating for blackjack by the book, and never mind that in highly complex systems no one can calculate the true odds the way you can for a casino game or even an NFL draft pick.)

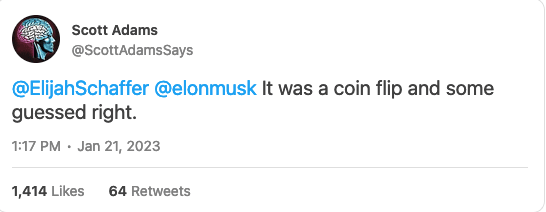

But Sam Harris was far from the only one. Here’s Dilbert creator Scott Adams explaining why even though he made a mistake in taking the mRNA shot, his process was not to blame:

He’s not defending his process as strongly as Harris, and he appeared to walk this back in this video, but the sentiment is largely the same: There was nothing wrong with my process, I just got unlucky, and others got lucky.

This is not an NFL analytics argument anymore — it’s a worldview shared by policymakers and powerful actors whose decisions have major consequences for human beings around the world. They seem to believe that as long as they come up with the correct heuristic (according to their own estimations and modeled after simplistic games of chance where it can be known in advance what heuristic was indeed better), whatever they do is justified. If reality doesn’t go the way they had expected, they still believe they acted correctly because when they simulated 100 pandemics their approach was optimal in 57 of them!

But the notion that someone with the correct heuristics, i.e., the proper model or framework for viewing the world as a game of dice, is a priori infallible is not only absurd, it’s perilous. Misplaced confidence, unwarranted certainty and being surrounded by peers who believe as you do that no matter what happens in reality, you can do no wrong incentivizes catastrophic risks no sane person would take if he had to bear the consequences of his misjudgment.

What started as a life hack to achieve better long term results — “focus on process, not outcomes” — has now become a religion of sorts, but not the kind that leads to tolerance, peace and reverence for creation, but the opposite. It’s a hubristic cult that takes as its God naive linear thinking, over-simplified probabilistic modeling and square-peg-round-holes it into complex domains without conscience.

If only this style of thinking were confined to a few aberrant psychopaths, we might laugh and hope none of them become the next David Koresh. Unfortunately this mode of understanding and acting on the world is the predominant one, and we see its pathology play out at scale virtually everywhere we look.